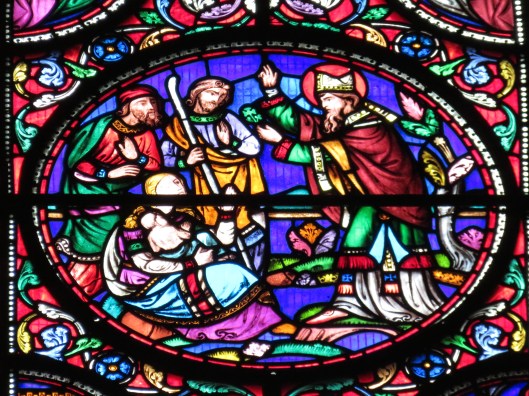

Stained glass window depicting Saint Patrick, Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, Ireland. Photo by Reliquarian.

Saint Patrick’s Day

Saint Patrick’s Day is celebrated each year on 17 March, the traditional feast day of Saint Patrick. Today, Saint Patrick is widely recognized as a patron saint of Ireland and is commonly associated with the color green. Saint Patrick, however, was not always identified with green in art. Historically, Saint Patrick was more commonly shown wearing blue, a color that continues to be affiliated with the saint. How, then, did green come to be associated with Saint Patrick? And what is the origin of “Saint Patrick’s blue”?

Captivity and Conversion

According to Butler’s Lives of the Saints, Saint Patrick was born about 389 CE to a Romano-British family.[1] When he was about 16, he was kidnapped by raiders and taken as a slave to Ireland.[2] He spent nearly 6 years in captivity there, during which time he found solace in prayer.[3] In his Confessio, Saint Patrick wrote, “In a single day I said as many as a hundred prayers and at night nearly as many.”[4]

Choir of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, Ireland. Photo by Reliquarian.

Eventually, Saint Patrick escaped from his master. After hearing a voice in his sleep, he fled nearly 200 miles to the coast where a ship carried him back across the sea to his family.[5]

Upon returning home, however, Saint Patrick received fresh visions and again heard voices, this time beseeching him to “come and walk among us once more.”[6] He resolved to return to Ireland to convert the people to Christianity, but before setting out, he undertook extensive study and preparation for the mission. Some sources suggest he spent several years studying in France (on the island of Lerins, off Cannes), while others suggest he also journeyed to Rome.[7]

Stained glass window depicting Saint Patrick (detail), Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin, Ireland. Photo by Reliquarian.

Banishment of Snakes

When Saint Patrick finally did return to Ireland, he traveled extensively, converting the people from paganism to Christianity. Several legends describe how he banished all snakes from Ireland and how he used a shamrock to explain the Trinity, though there is scant evidence to support these stories. Still, the popularity of these stories persists. At Trinity College Dublin, for example, the school’s famous Campanile features four figures, sculpted by Thomas Kirk, representing the faculties of Law, Medicine, Science, and Divinity. Medicine is represented by a figure bearing a simple staff rather than a caduceus—a staff entwined by two serpents, which is now a common symbol of the medical profession. The snakes are missing from Medicine’s staff, we were told by our student guide, because Saint Patrick banished snakes from Ireland in the fifth century![8]

Trinity College Campanile (detail) depicting Medicine, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland. Note the figure of Medicine his holding a bare staff rather than a caduceus — apparently because Saint Patrick banished all snakes from Ireland. Photo by Reliquarian.

Shamrocks and the Trinity

The legend of Saint Patrick’s use of the shamrock to convert the Irish also remains popular. According to the story, upon returning to Ireland in 433 CE, Saint Patrick first confronted the Druids on the Hill of Slane in what is now County Meath.[9] Saint Patrick had resolved to celebrate his first Easter back in Ireland by lighting the Paschal fire on Easter eve.[10] Unbeknownst to Patrick, Loigaire (or Lóegaire), the High King of Ireland, had decreed that no other fire should be lit while a festival fire burned at his own palace on the Hill of Tara nearly 10 miles away.[11] The story suggests Easter and the pagan festival of Beltane happened to coincide in 433 CE, though as J.B. Bury points out, the day of Beltane was celebrated on the first day of summer, not the vernal equinox as indicated in the story.[12] “The calendar is disregarded,” Bury concludes dryly.[13]

Spying the fire burning on the Hill of Slane, Loigaire and his court were surprised and alarmed. The king consulted his magicians, who replied, “O king, unless this fire which you see be quenched this same night, it will never be quenched; and the kindler of it will overcome us all and seduce all the folk of your realm.”[14] The king then traveled by chariot to the Hill of Slane with the queen, his two chief sorcerers, and several others to confront the man responsible for lighting the fire. After an altercation, the king ordered that Saint Patrick be seized. According to J.B. Bury’s account, Patrick then cried out, “Let God arise, and let his enemies be scattered.”[15] Then, “a great darkness fell and the earth quaked, and in the tumult the heathen fell upon each other, and the horses fled over the plain.”[16]

Saint Patrick’s Window (detail), Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin Ireland. This panel depicts Saint Patrick at Tara. Photo by Reliquarian.

Bury remains skeptical of the ancient account, though he admires the cleverness of the storytelling. “The framers of this legend had an instinct for scenic effect,” he notes.[17] Butler’s Lives of the Saints expresses a similar dubiousness while admitting the story might hold a kernel of truth. The Lives of the Saints states, “There is doubtless much that is purely mythical in the legend of the encounter of Patrick with the magicians or Druids, but it is clear that something momentous was decided on that occasion, and that the saint, either by force of character or by the miracles he wrought, gained a victory over his opponents which secured a certain amount of toleration for the preaching of Christianity.”[18]

Statue of Saint Patrick (detail), Hill of Tara, County Meath, Ireland. Saint Patrick is shown holding a shamrock in his right hand. According to legend, the saint used a shamrock to explain the Trinity to the people of Ireland. Photo by Reliquarian

Other legends, probably of more recent vintage, suggest Saint Patrick used the shamrock to explain the nature of the Trinity during his evangelization of Ireland. If he did, the shamrock likely would have made a convenient pedagogic device. The triskele or triskelion—a triple spiral symbol sometimes contained within a circle—was a common motif in Celtic art, and it continued to be used in Christian art of Ireland from at least the seventh century onward.[19] Roger Homan observes, “We can perhaps see St Patrick drawing upon the visual concept of the triskele when he uses the shamrock to explain the Trinity, being both one leaf and having three lobes.”[20]

Saint Patrick’s Window (detail), Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin Ireland. Note the shamrocks in Saint Patrick’s left hand. Photo by Reliquarian.

Blue Period

Today, green is the color most commonly associated with Saint Patrick, but this was not always the case. Kassia St. Clair indicates in her book The Secret Lives of Color, “Strangely, . . . the color he was most associated with until the middle of the eighteenth century was a shade of blue.”[21] St. Clair explains that in response to the perceived anti-Catholic bias of William of Orange and orange-wearing Protestants, Catholics craved their own symbolic color.[22]

Entrance Passage to Newgrange, County Meath, Ireland. Built around 3,200 BCE, the passage tomb at Newgrange is older than pyramids at Giza in Egypt. The large entrance stone in front of the passage features megalithic designs, including triskele-like spirals on the left side of the stone. Photo by Reliquarian.

Blue had long signified authority in Ireland. In the 13th century Armorial Wijnbergen, for example, Le Roi d’Irlande (King of Ireland) is identified with a blue shield bearing a gold harp.[23] Early depictions of Saint Patrick, including in various medieval manuscripts, also presented the saint in blue. Centuries later, in 1783, when King George III created the Order of Saint Patrick, a new order of chivalry for the Kingdom of Ireland, a shade of sky blue known as Saint Patrick’s blue was chosen to identify the order.[24] By then, however, Saint Patrick’s association with blue had begun to lose its allure. An article in Smithsonian Magazine explains, “From the late 18th to the 20th century, as the divide between the Irish population and the British crown deepened, the color green and St. Patrick’s shamrock became a symbol of identity and rebellion for the Irish.”[25]

Today, shades of blue continue to be used to identify Saint Patrick and Ireland in some contexts. The standard of the President of Ireland, for example, is a deep azure, while the robes of the choir of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin are a lighter shade of Saint Patrick’s blue. Still, green has undoubtedly replaced blue as Saint Patrick’s color in modern times.

Relics of Saint Patrick

Relics of Saint Patrick can be found throughout Ireland. One of the most important, the Bell of Saint Patrick, is currently on permanent display at the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin. According to the museum, the bell is a “powerful relic” which is “frequently mentioned in written sources as one of the principal relics of Ireland.”[26] The museum further notes that “[i]t was also used as a political tool, to legitimise Armagh as the most important Christian site in Ireland through its association with St. Patrick.”[27] Saint Patrick served as the first Bishop of Armagh.

Bell of Saint Patrick, National Museum of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland. Photo by Reliquarian.

A shrine that once contained the bell is also on display in the museum’s treasury. The shrine, which dates to approximately 1100 CE, is trapezoidal, matching the shape of the bell, and is formed from plates of bronze.[28] At one time, the shrine was once covered with thirty panels of decorative gold filigree.[29]

Shrine of the Bell of Saint Patrick, National Museum of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland. Photo by Reliquarian.

Another shrine that once belonged to Saint Patrick is also kept at the museum. The Domhnach Airgid Shrine, or “silver church” shrine, was given by Saint Patrick to Saint Macartan, the founder of a church in Clogher in County Tyrone. Part of an ancient manuscript of the Gospels was discovered inside the shrine when it was opened in the 19th century. Originally fashioned in the 8th century, the shrine was subsequently reworked in the mid-1300s. Today, a panel of the shrine (the one on the lower left) depicts Saint Patrick delivering the shrine to Saint Macartan.

Domhnach Airgid Shrine, National Museum of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland. Photo by Reliquarian.

In 1901, a stone slab decorated with a Celtic cross was recovered near Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin. A sign beneath the stone indicates it may once have covered Saint Patrick’s Well, the well at which Saint Patrick baptized his converts. Some believe the well itself can be found near Trinity College.[30] Nassau Street, which runs along the college, was once known as “Sráid Thobar Phádraig” or “Street of Saint Patrick’s Well.”[31]

Discovered in 1901, this stone slab bearing a Celtic cross is believed to have once covered Saint Patrick’s Well, the well used by Saint Patrick to baptize converts. Today it is on display at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin. Photo by Reliquarian.

Conclusion

Today, images and references to Saint Patrick can be found throughout Ireland and the world. Whether clad in green, blue, or some other color, his significance to the Irish people has been enduring.

Statue of Saint Patrick, Hill of Tara, County Meath, Ireland. Photo by Reliquarian.

[1] 1 Butler’s Lives of the Saints 612-13 (Herbert J. Thurston, S.J. & Donald Attwater eds., 2d ed. 1956.

[2] Id. at 613.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] Id. 613-14.

[6] Id. at 614.

[7] Id.

[8] We’ve noticed that some sources identify the figure with the staff as Science rather than Medicine and claim the figure with a book is Medicine instead. As noted, our tour guide specifically identified the figure with a staff as Medicine. We further note that the figure with the book is also holding a telescope and a compass, making her a more likely candidate to represent Science rather than Medicine.

[9] See J.B. Bury, The Life of Saint Patrick and His Place in History (1905).

[10] Id. at 104.

[11] Id.

[12] Id. at 107.

[13] Id.

[14] Id.

[15] Id. at 106.

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] Butler, supra note 1, at 614.

[19] See Roger Homan, The Art of the Sublime (2017).

[20] Id.

[21] Kassia St. Clair, The Secret Lives of Color 223 (2016).

[22] Id.

[23] See Ewan Morris, Our Own Devices (2005).

[24] See Shaylyn Esposito, “Should We Be Wearing Blue on St. Patrick’s Day?,” Smithsonian Magazine (Mar. 17, 2015), https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/should-st-patricks-day-be-blue-180954572/.

[25] Id.

[26] “Bell of St Patrick and Its Shrine,” National Museum of Ireland, https://www.museum.ie/en-IE/Collections-Research/Collection/Resilience/Artefact/Test-5/8e122ba9-6464-4533-8f72-d036afde12a9.

[27] Id.

[28] Id.

[29] Id.

[30] “Trinity’s Little Secret: Saint Patrick’s Well (Sráid Thobar Phádraig),” Trinity College Dublin (Mar. 16, 2018), https://www.tcd.ie/news_events/articles/trinitys-little-secret-saint-patricks-well-sraid-thobar-phadraig/.

[31] Id.