Tags

Altar of the Holy Blood, altarpiece, church, Friedrich Herlin, Germany, martyr, pilgrimage, relic, Rothenburg, Saint James, Santiago de Compostela, tomb

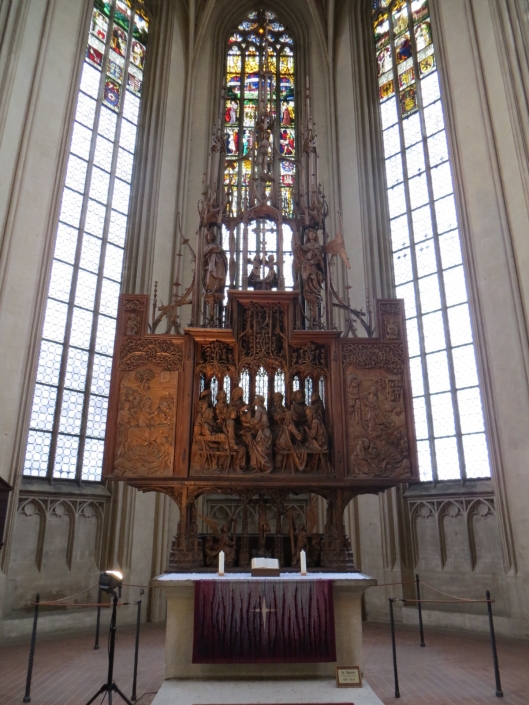

Twelve Apostles Altar, Church of Saint James (St. Jakobskirche), Rothenburg ob der Tauber, Germany. Photo by Reliquarian.

The Way of Saint James

According to tradition, Saint James, one of the twelve Apostles, was martyred by beheading in the year 44. After the rediscovery of his relics in 814, pilgrimages to his tomb in Compostela, northern Spain, became extremely popular. Compostela even rivaled Jerusalem and Rome as a destination for pilgrim travelers during the Middle Ages. Consequently, routes to Saint James’s shrine, including one through Rothenburg, Germany, crisscrossed Europe, marking the path to the saint’s tomb. Today, the Way of Saint James (Camino de Santiago) continues to direct travelers to the remains of the fiery-tempered Apostle whom Jesus once called a “Son of Thunder.”

Invitation to a Beheading

Saint James was beheaded in Jerusalem during the Christian persecutions of King Herod Agrippa I. According to Clement of Alexandria, Saint James’s accuser was so moved by the courage and conviction James showed at his trial that he subsequently repented and declared himself a Christian. As a consequence, the man was sentenced to be beheaded alongside Saint James. As both men were led to execution, the accuser turned to James and begged for his forgiveness. According to Butler’s Lives of the Saints, “St James, after pausing a little, turned to him and embraced him, saying, ‘Peace be with you’. He then kissed him, and they were both beheaded together.”[1]

A Tomb by the Sounding Sea

Isenheim Altarpiece, Matthias Grunewald (sculptures by Nicolas of Hagenau) (detail), 1510-1515, Colmar, France. On the carved predella of the Isenheim Altarpiece, Saint James can be seen holding a large seashell in his right hand. His pilgrim’s cap is also adorned with a shell. Photo by Reliquarian.

Early chronicles suggested that after his death, Saint James’s remains were transported from Jerusalem to the northern coast of Spain where they were buried contra mare Britannicum, “close to the British sea.”[2] The location of the tomb, however, remained a mystery until, centuries later, in about 814, the tomb was rediscovered under miraculous circumstances.[3] According to legend, a local monk named Pelayo was guided by a star to a secluded spot in the woods near the Galician coast.[4] There he discovered a marble sarcophagus that contained human bones, apparently very old.[5] Bishop Teodomir, the local bishop, proclaimed the remains to be those of Saint James, long believed to have been buried in the region. After learning of the discovery, King Alfonso II journeyed to the site to venerate the relics and ordered that a church be built on the spot. The modest church established by King Alfonso II later grew into the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, the ultimate destination of pilgrims traveling the Way of Saint James.

King Alfonso II’s journey to the tomb of Saint James is considered the first pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, and it set the example for subsequent generations of pilgrim travelers. Departing from Oviedo, the location of his royal court, King Alfonso II likely took the Roman road known as the Camino Primitivo to Compostela. As the popularity of Saint James’s shrine grew, other routes gradually came into regular use, such as the Camino del Norte, another Roman road, which skirted the coast. By the 11th century, the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela had become an international phenomenon, drawing visitors from all over Christendom and establishing Santiago de Compostela as a rival to Jerusalem and Rome for pilgrims.[6] In a paper discussing the history of the pilgrimage, Laurie Dennett opines that interest in Saint James’s relics had begun to shift the “conceptual geography of Christian Europe, giving it a new pole in the west, a new focus for popular devotion, that balanced the Byzantine east with its spiritual centre at Jerusalem.”[7] She further notes that “Santiago de Compostela even seemed to rival the pretensions of Rome,” at least for a time.[8]

St. Jakobskirche and the Twelve Apostles Altar

The St. Jakobskirche (Saint James’s Church) in Rothenburg ob der Tauber was once an important stop on the pilgrimage road to Santiago de Compostela. Known more widely as the home of the Altar of the Holy Blood, the church also houses the impressive Twelve Apostles Altar (Zwölfbotenaltar), a carved altarpiece with a painted predella and painted wings, which incorporates several images of Saint James.

View of St. Jakobskirche from the city walls. Photo by Reliquarian.

Completed in 1466, the altarpiece is the work of Hans Waidenlich and Friedrich Herlin with carvings in the Multscher tradition by an unknown sculptor.[9] Herlin, who may have been from Rothenburg, moved to Nördlingen later in his career and is closely identified with the Twelve Apostles Altar, which he signed: “This work was made by Friedrich Herlin, painter, mcccclxvi. Saint James pray to God for him.”[10]

In Carved Splendor: Late Gothic Altarpieces in Southern Germany, Austria, and South Tirol, Rainer Kahsnitz identifies the Twelve Apostles Altar as “one of the best-preserved altarpieces from the Late Gothic period.”[11] Although little is known about the origins of the altarpiece, Kahsnitz speculates that it must have replaced an earlier work at St. Jakobskirche.[12]

Twelve Apostles Altar (detail). Photo by Reliquarian.

The corpus of the altarpiece depicts the Crucifixion, with Mary (to the left) and Saint John the Evangelist (to the right) below the cross, flanking the dying Christ. Next to Mary stands Saint James wearing a pilgrim’s hat decorated with a scallop shell, a symbol of pilgrimage. Two other shells dangle from his wrist, and he is shown with a pilgrim’s staff, another defining attribute of the patron saint of pilgrims.[13] The other carved figures below the cross are Saint Elizabeth (to the far left), who is carrying a loaf of bread and a pitcher; Saint Leonard (next to Saint John), the patron saint of prisoners of war; and Saint Anthony the hermit (to the far right), who is shown with a bell. According to Kahsnitz, the altar was kept permanently closed following Rothenburg’s adoption of the Reformation.[14] This helped preserve the sculptures and the paintings on the inner wings.[15]

Saint James and Saint Peter. Friedrich Herlin’s predella depicts Saint James with his traditional attributes in art: a pilgrim’s staff and a seashell. To the right of Saint James is Saint Peter with several of his symbols: a set of keys and a book. Photo by Reliquarian.

Saint James appears again on Herlin’s predella with a shell in one hand and a pilgrim’s staff in the other. To his left, Saint Peter carries two of his traditional attributes: a set of keys and a book, which he peers into with the aid of spectacles. All twelve Apostles are represented on the predella, arranged in pairs behind a Late Gothic balustrade.[16] In addition to other paintings, the back of the predella also features a depiction of the veil of Saint Veronica: the image of Christ’s face with a crown of thorns imprinted on a veil or shroud.[17]

Sons of Thunder

Saint James is often known as “the Greater” to distinguish him from Saint James, son of Alphaeus, known as “the Lesser.” He was the son of Zebedee and brother of Saint John the Evangelist, and he was the first Apostle martyred. Saint James and his brother John apparently earned the epithet Boanerges, or “Sons of Thunder,” on account of their “impetuous spirit and fiery temper.”[18] Nevertheless, as noted in Butler’s Lives of the Saints, James, John, and Peter, the Apostles “who from time to time acted impetuously, and had to be rebuked, were the very ones our Lord turned to on special occasions.”[19] James, John, and Peter were the only Apostles to witness the agony in the garden of Gethsemani and were the only ones present for the Transfiguration.

Modern Pilgrims

The Way of Saint James continues to be a popular with pilgrims even today. According to the Confraternity of Saint James, an organization founded “to bring together people interested in the medieval pilgrim routes through France and Spain to Santiago de Compostela,” the last several decades “have seen an extraordinary revival of interest in the pilgrimage to Santiago.”[20] Once considered “one of the greatest of all Christian shrines” in the Middle Ages,[21] the route from the border of France and Spain known as the Camino Francés was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993.[22]

Twelve Apostles Altar, Church of Saint James (St. Jakobskirche), Rothenburg ob der Tauber, Germany. Photo by Reliquarian.

Still, some scholars question whether Saint James ever preached in Spain and whether the remains interred at Santiago de Compostela really are those of Saint James. Butler’s Lives of the Saints states, “Outside of Spain almost all eminent scholars and critical students of history answer both questions in the negative.”[23] Several authors have argued that Saint James’s visit to Spain is “improbable” because Saint James was martyred in Jerusalem in the year 44 and because he was “unheard of in Spain before the end of the seventh century.”[24] Additionally, while it may be “quite possible that the relics recovered, after they had been lost, are identical with those which were venerated at Compostela in the middle ages, . . . the authenticity of medieval relics is always difficult to establish and in this case it is more than dubious.”[25]

Nevertheless, thousands of people continue to follow the Way of Saint James to Santiago de Compostela each year. While there are “as many reasons for this revival as there are pilgrims,” the Confraternity of Saint James observes that “many people make the pilgrimage at a turning point in their lives, and . . . many are helped to come to terms with personal crisis by a period of separation from all that is familiar, and the shared hardship of the road.”[26]

Pilgrim’s Hat, felt, silk braid, shell, bone, jet (c. 1571). This pilgrim’s hat is currently on display at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, Germany, along with a matching pilgrim’s cloak and staff. The matching set of pilgrim’s garb belonged to Stephan Praun III, a pilgrim to Santiago de Compostela. Photo by Reliquarian.

Saint James the Greater, pine with paint and gilding, South German (1475-1500), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The influence of Veit Stoss, who worked in Nuremberg and Krakow, is evident in the carving of the statue’s robes and face. Photo by Reliquarian.

[1] 3 Butler’s Lives of the Saints 183 (Herbert J. Thurston, S.J. & Donald Attwater eds., 2d ed. 1956).

[2] Laurie Dennett, “2000 Years of the Camino de Santiago: Where Did It Come From? Where Is It Going?,” The Confraternity of Saint James, http://www.csj.org.uk/2000-years.htm (citing martyrologies by Florus of Lyons and Usuard of St. Germaine-des-Prés). Dennett observes that “by the late 8th century, a literary tradition had developed which held that the burial place of St James lay in Spain, even if the site had not yet been identified.” She further notes, “Interestingly, it was not until after the purported discovery of the tomb in about 814 that a corresponding tradition evolved concerning the Apostle’s return to Palestine and death, and the transportation of his mortal remains back to Spain for burial.” Id. The mare Britannicum is the present-day English Channel.

[3] See id.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] See Rainer Kahsnitz, Carved Splendor: Late Gothic Altarpieces in Southern Germany, Austria, and South Tirol 58 (2006). Kahsnitz explains that the sculptures “were executed by a carver from the circle around the Ulm sculptor Hans Multscher (active there from 1427 until his death in 1467). In their compact three-dimensionality they are based more strongly on Multscher’s earlier works from the 1450s, at which time the sculptor was probably Multscher’s pupil.” Id. at 61.

[10] Id. at 58. A clever Latin inscription on the frame of the altarpiece also dates the work to 1466. It begins, “Bis duo c quoque sexagintaque sex quoque mille . . . .” Id.

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] See George Ferguson, Signs and Symbols in Christian Art 112 (1959). Ferguson observes that the pilgrim’s staff is “used alone and in combination with various other objects as an attribute of numerous saints who have been noteworthy for their travels and pilgrimages.” Id. Other saints commonly depicted with staffs include Saints Christopher, John the Baptist, Jerome, Philip the Apostle, Ursula, and Roch. Id.

[14] Kahsnitz, supra note 9, at 58.

[15] Id.

[16] Id. at 60.

[17] See, e.g., Rosa Giorgi, Saints in Art 119 (Stefano Zuffi ed. & Thomas Michael Hartmann trans., 2002).

[18] Butler’s Lives of the Saints, supra note 1, at 182.

[19] Id.

[20] The Confraternity of Saint James, The Confraternity of Saint James, http://www.csj.org.uk/csj.htm; The Present-Day Pilgrimage, The Confraternity of Saint James, http://www.csj.org.uk/present.htm.

[21] Butler’s Lives of the Saints, supra note 1, at 183.

[22] The Present-Day Pilgrimage, supra note 20.

[23] Butler’s Lives of the Saints, supra note 1, at 183.

[24] Id.

[25] Id.

[26] The Present-Day Pilgrimage, supra note 20.